![]()

Pitching can't win championships on its own. Somebody's gotta score runs.

Few teams have struggled to score runs over the course of 2014 like your New York Mets have. The issue has only become more glaring since the All-Star break, evidenced by the team’s .643 OPS (29th in the majors) and 204 runs scored (25th).

Pitching doesn’t win championships. Not alone, anyway.

The arrival and potential emergence of a few heralded, non-pitching minor leaguers have, fortunately, bestowed a justifiable excuse for excitement in Flushing.

We witnessed the most recent recalls of infielder Wilmer Flores and outfielder Matt den Dekker in May and August, respectively. Second baseman Dilson Herrera, of lesser fanfare, was next in line.

Ideally, the trio signifies the first cogs of an impending influx of position-player talent that the organization hopes will begin producing at Citi Field sooner rather than later.

With an injury-marred roster, this look should at least provide the Mets with some idea of what they possess regarding their plans for the foreseeable future. This is especially important as the franchise prepares to enter another offseason defined by an uninspiring crop of free-agents-to-be and overt financial limitations.

Whether the affordable, team-controlled assets become run-scoring and dependable everyday players remains to be seen. The Mets know the apparent strengths and weaknesses of Flores and den Dekker, and their minor league resumes largely speak for themselves. The extraordinarily rapid ascent of Herrera, though, leaves his unavoidably scant in relation.

Before moving on, let's delve a bit deeper into why the Mets may have found a genuine starting infielder in Herrera while few are taking notice.

Dilson Herrera

Herrera — who, until recently, has managed to fly under the radar— appears to have bought into the new organizational hitting philosophy while making a prolonged mockery of minor league pitching this year, culminating in his major league debut at just 20 years old.

General manager Sandy Alderson was quietly lauded for the acquisition of Herrera last year. For example, Baseball America’s Matt Eddy heaped praise on the small second baseman, despite Herrera's absence from any of the publication’s own annual prospects lists.

A compactly-built 5-foot-10, Herrera makes consistent line-drive contact and ought to develop at least average power to go with a solid average and on-base percentage.

He lacks the type of flashy defensive tools to get a look at shortstop, though sticking at the keystone will be no problem thanks to solid range and quick hands. As such, South Atlantic League managers recently selected Herrera as the best defensive second baseman in the circuit.

So where’s the excitement? Longtime super-prospect Flores may have already been a three-year MLB veteran by now with that profile, given the reality of his well-documented defensive deficiencies.

Since playing himself into a promotion from St. Lucie to Binghamton (making him the youngest player in the Eastern League at the time of his call-up), the 20-year-old Herrera mashed Double-A pitching to the tune of a .967 OPS in 278 plate appearances.

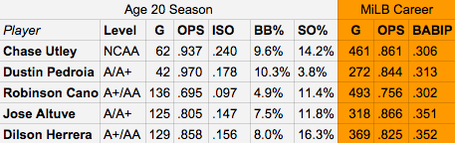

Amazin’ Avenue’s own Steve Schreiber interestingly points out that if Herrera’s minor league assault is any indication of future success, it wouldn’t be the first time the prospect community largely missed the mark on a future quality second baseman.

I've compiled a table below to illustrate where Herrera is on the development curve and how his production stacks up with that of a few of baseball’s top second basemen at the same age:

![Screen_shot_2014-09-12_at_5.03.56_pm_medium]()

As an aside, the first thing that stood out to me are Robinson Cano's minor league numbers. To a certain extent, it’s no wonder he wasn’t grouped with the game’s top prospects as a minor leaguer. I suppose it also goes to show just how imprecise the science behind projecting young ballplayers can be.

Getting back to Herrera, his high batting average on balls in play can be construed as something of a red herring, attributable to a bit of good fortune in the batter’s box. But it could alternatively be a result of consistently strong contact.

Otherwise his numbers are—almost unbelievably—quite comparable across the board, and even more impressive when you account for Herrera’s mostly mediocre St. Lucie numbers (.765 OPS).

MLB's youngest player has understandably struggled since his debut, posting a .189/.271/.340/.611 line in 53 plate appearances.

Close Behind

Amid the warranted hype surrounding the organization’s wealth of young pitching, it’s evident that the organization has taken tremendous strides elsewhere of late, bolstering their minor league system with talent around the diamond.

Of the four Mets farmhands to crack Keith Law’s midseason top 50 prospects list—Noah Syndergaard (No. 16), Michael Conforto (No. 32), Brandon Nimmo (No. 34), and Dominic Smith (No. 49)—three were position players.

What’s more, while Conforto and Smith are absent from midseason rankings compiled by Baseball America, a source of virtually equal repute, catcher Kevin Plawecki appears at No. 40.

Shortstop Matt Reynolds, while a few years older than Herrera, has displayed an unequivocal ability to handle Triple-A pitching.

Should Reynolds continue to progress like Herrera has, it won’t be long before he too earns himself a legitimate look with the parent club, with other prospects ever-closer behind.

The 23-year-old hasn’t dominated in the thin air of Las Vegas the way Flores did in the 55 games before his promotion (.323/.367/.568). And while Reynolds isn't much of a power hitter, he is posting an impressive .882 OPS.

It certainly doesn’t take much to outperform the team’s current options at shortstop, and according to Andy Martino of the Daily News, at least one scout believes Reynolds is already capable of doing so.

Las Vegas teammates are impressed by out-of-nowhere infield prospect Matt Reynolds, with some saying he is both a better hitter and fielder than Ruben Tejada. Added one rival evaluator, comparing Reynolds to Wilmer Flores at short: ‘Better hands, comparable range.’

On the other hand, Mets Minor League Blog’s Toby Hyde is unsure of to what Reynold’s emergence should be attributed. He notes an increase in BABIP and BB% as possible signs of better fortune, stronger contact, and an improved eye, but feels that his uptick in strikeouts and limited display of power project a modest hitter at best.

It’s suggesting that he will get on base at an above average rate and hit for below average power. This is Ruben Tejada’s game. This is Cliff Pennington’s game.

If we plug a .350 BABIP and a 20 percent strikeout rate into Reynolds’ power production in Double-A, we get something like .275/.350/.341 that’s playable at short, but nothing more.

Either way, the not-so-immediate future bodes considerably, and increasingly, brighter.

The majority of the organization’s lauded non-pitching talent is still getting acquainted with the daily grind of professional baseball and is likely a couple of years from cracking a major league roster. Others, like Plawecki, may be ready to make the jump and provide something close to serviceable production, but are either blocked or would be pressed for consistent playing time due to present circumstances in Queens.

Still, the rate of their organizational ascent may largely depend on how the recent call-ups fare in the big leagues. Flores, no stranger to hype, has been ranked as high as number 47 overall by Baseball America in 2008. That’s higher than any of the premier second basemen profiled above ever were.

Flores is a third baseman by trade, but his best chance to stick in the major leagues appears to be at a middle infield position. There, the Mets hope Flores's offensive prowess will outweigh his presumed shortcomings defensively.

In his first consistent stint as a big league starter, Flores’s glove at shortstop has been a pleasant surprise; but he’ll have to do better than a .667 OPS (in 233 PA) in order to stick around. Fortunately, he's been scolding in the month of September, putting up a nine extra-base hits and an OPS of .967.

Until that comes to fruition, Flores is on notice with internal options like Herrera and Reynolds nipping at his heels. The same can be said of Ruben Tejada, whose situation appears even more dire.

den Dekker, 26, had similarly been on the big league precipice for a couple of seasons now, failing to find his stroke in a 27-game major league stint in 2013. He’s struggled mightily this year at the dish in a 45-game sample, hitting to a .596 OPS in 141 plate appearances and continuing to leave much to be desired despite an exemplary glove.

What It Could All Mean

The point is, pitching doesn’t win championships (my disdain for spurious cliches aside). Only a team’s notably consistent ability to score more runs than they concede can do that.

MLB's fourth-best 3.27 ERA owned by the 67-78, Octoberless-baseball-bound San Diego Padres' starting pitching staff is proof positive.

In fairness, the odds of players like Herrera and Reynolds amounting to more than league-average infielders are admittedly slim, as is the case with most every prospect. Their recent play, however, has begun to turn heads, in spite of any general scouting consensus prior to the 2014 season.

Through prudence, patience, and keen drafting, the Mets have garnered a pool of young pitching talent to rival that of any other franchise. A surplus of this nature is quite possibly the most valuable commodity a franchise can possess, both in terms of necessary depth and trade value.

The sooner the aforementioned young bats have an impact at the major league level, the more flexibility the organization will have with those players and their wealth of quality young arms. Contributions from these young hitters—in addition to adding to their trade value—would help resolve the team's offensive ineptitude and put an increasingly expeditious stamp on the franchise's longstanding futility.