The Mets of 1973 had a starting lineup vastly different from the one that stunned the baseball world back in 1969. However, this team had a similar September surge and found themselves in the World Series despite a mediocre 82–79 regular season record.

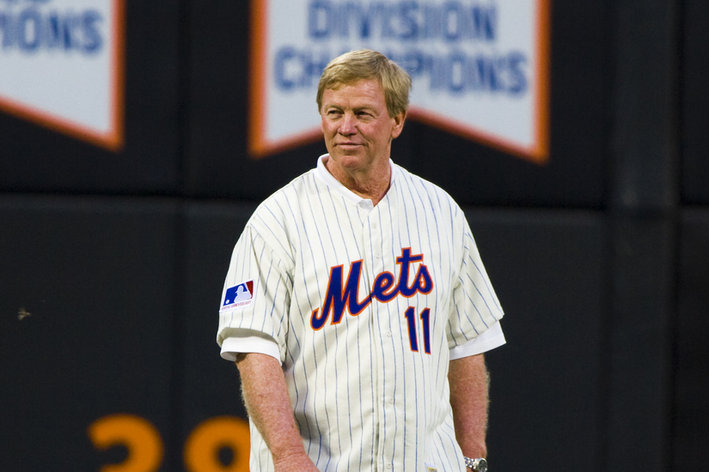

Like the Miracle Mets that defeated the Baltimore Orioles to win the crown, the ’73 team was led by an outstanding starting pitching staff. Of course, there was the duo of Tom Seaver—who would win his second Cy Young Award—and Jerry Koosman. The youngster of the group was lefty John Matlack—winner of the 1972 Rookie of the Year and arguably New York’s top pitcher in the season’s final few weeks. Newcomer George Stone would have the best winning percentage in the starting rotation thanks to a 12–3 record.

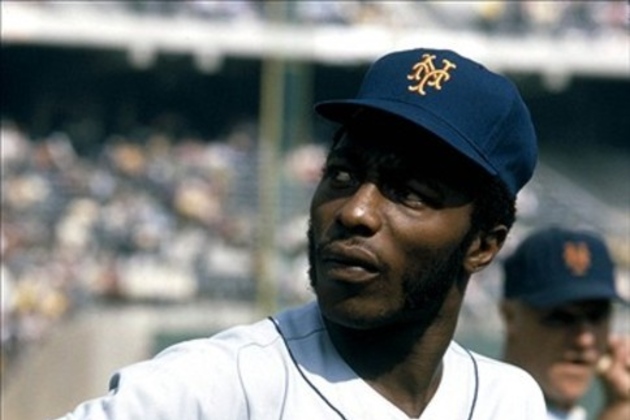

Manning the bats were first baseman John Milner and third baseman Wayne Garrett, as well as outfielders Cleon Jones and Rusty Staub, while shortstop Bud Harrelson and second baseman Felix Millan made up a solid middle infield. Providing more leadership than performance was the legendary (and past his prime) Willie Mays, who was acquired via trade with San Francisco in the middle of the 1972 season.

But few of those players were able to remain healthy throughout the season for manager Yogi Berra, who was in his second year at the helm after taking over for the late Gil Hodges. Milner, Jones, Harrelson, and Millan were just a few of the names that spent significant time on the mend and out of the lineup. In fact, injuries were the main reason Berra’s club sat in last place at 34–46 and ½games back of first on July 8. By late August they were still in the cellar of the six-team National League East—certainly failing to meet the expectations of Mets fans and management.

Team chairman M. Donald Grant held a clubhouse meeting. In the middle of his pep talk, relief pitcher Tug McGraw interrupted by shouting the now-famous words “Ya Gotta Believe!” Little did anyone in that room realize the eventual significance of that statement. It quickly became their rally cry, and right about this time 40 years ago the Mets began their charge up the standings in a division that nobody was running away with.

On August 30 they were six-and-a-half games back at 61–71. By September 16 they were 73–76 and had sliced the deficit by four games thanks to a roster that was now much healthier. This sudden thrust into the pennant race was the genesis for the quotable Berra to utter his most notable line: “It ’aint over ’til it’s over.” One day later, the Mets began a critical stretch of five straight games against the division-leading Pittsburgh Pirates.

After splitting a pair at Three Rivers Stadium, the teams made their way to Shea. It proved to be a fortuitous venue for the Mets, especially on September 20. The top of the 13th ended with the “Ball on the Wall Play.” Dave Augustine drilled a Ray Sadecki pitch to deep left with Richie Zisk on first. It hit the top of the fence, remained in play, and bounced perfectly to Jones who relayed it to Garrett, who in turn threw home to catcher Ron Hodges. The throw was a perfect one-hop, chest-high strike and nailed Zisk at the plate. New York went on to win, 4–3, in the bottom half of the 13th inning, then went on to win the next night, 10–2, behind a complete game by Seaver to sweep the home series with the Pirates and move into first place by a half game (at 77–77).

The Mets didn’t look back from there as they won five of their final seven games. On October 1, Seaver got his 19th victory of the season and McGraw came in for the save to lock up the division title with a 6–4 decision against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. With it, their winning percentage of .509 became the lowest of any pennant-winning club. But by winning 27 of their last 39, this was tale of a team that got hot—and healed—at the right time.

Jones was the top performer on offense down the stretch with six home runs and 14 runs batted in over the final 10 games. McGraw rebounded from a rough start to the season to go 5–0 with 12 saves and an earned run average of 0.88 in 41 innings that spanned the last five weeks.

As the curtain drew on the regular season, New York found itself in the National League Championship Series against what appeared to be a far superior Cincinnati Reds team that had 17 more regular season victories and were heavy favorites make their second straight World Series appearance. On paper, the Mets were clearly overmatched.

Pitching was the key in the NLCS, as Cincinnati managed just two runs and eight hits over the first two games at Riverfront Stadium. Still, the teams had won one game apiece as the series shifted to Queens.

Following a 5–0 New York win in Game 2, Harrelson became the target of Reds players due to comments in which he criticized his opposition’s offensive futility. In the middle of turning a double play at second base during the fifth inning of Game 3, Harrelson met by a hard-sliding Pete Rose. The two began shoving one another, which quickly escalated into an all-out brawl that fired up both teams and enraged Mets fans (their throwing of debris on the field nearly resulted in a forfeit).

When matters calmed down, New York got a another stellar pitching effort, this time by Koosman. The southpaw went the distance while Staub cracked two home runs to boost the Mets to a 9–2 victory and a 2–1 lead in the best-of-five series.

Villain Rose got his revenge the next day in Game 4 with a 12th-inning home run off Harry Parker, which meant a deciding fifth game would be played in Flushing. In that game, the Mets broke open a 2–2 tie with four runs in the bottom of the fifth to back starter Seaver. Key hits by Garrett, Jones, and Mays helped New York take a 7–2 lead into the ninth.

With fans eager to celebrate and Seaver still on the mound, the Reds loaded the bases which prompted Berra to call on McGraw to spell the tiring No. 41. The rejuvenated left-handed relief ace did his job in a crucial spot, getting Joe Morgan to pop out and then inducing a ground ball to first out of Dan Driessen. Milner tossed to McGraw covering the bag just as the crowd was storming the field in droves.

Amid the mob scene beneath, the Shea Stadium scoreboard displayed a message which perfectly captured the moment:

“Guess who’s 1973 National League Champion…Would you believe the NY Mets. Well you better believe.”

It was hard not to continue to believe in this team, even as they traveled across the country to the Bay Area to face the defending champion Oakland A’s in the World Series. Once again, the Mets weren’t given much of a chance.

After Matlack came out on the short end of a 2–1 pitchers’ duel in the opener, New York was able to bounce back with a wild extra-inning win in Game 2. It was a contest that featured a controversial play at home plate in the top of the 10th in which Harrelson was allegedly tagged out trying to cross the plate by catcher Ray Fosse on a would-be sacrifice fly. The unfortunate image of Mays stumbling twice in the outfield was more than offset by his coming through with what turned out to be the game-winning single in the 12th off Rollie Fingers. The game took four hours and 13 minutes for the Mets to even the series at one—the longest World Series game ever at the time.

Seaver pitched before the home crowd in Game 3 and was staked to an early 2–0 lead. He allowed the A’s to plate a run in the sixth and then one in the eighth, and McGraw was able to preserve the tie through the ninth and into the 10th. Catcher Jerry Grote’s passed ball on a strike three pitch by Harry Parker allowed batter Angel Mangual to safely get to first base and advanced Ted Kubiak to second. The error proved costly as Bert Campaneris’s RBI single was the difference in Oakland’s 3–2 win.

Rusty Staub got New York back on track the next night, driving in five runs on four hits (including a first-inning three-run homer), all despite an aching shoulder suffered in the NLCS. Matlack got the win by allowing just one run in eight frames, and the Mets were poised to take the series lead with Game 5 at home.

They did just that, as Koosman and McGraw combined to shut out the A’s and prevail, 2–0. Yet again, it appeared that Queens was playing host to a team of destiny.

But unlike in 1969, the Mets came up one victory short of completing another unlikely rise to the top of the baseball world. Oakland captured its second straight title by winning the final two at home, beating Seaver and Matlack, respectively. Home runs by Campaneris and series MVP Reggie Jackson in the third inning of Game 7 put Oakland up to stay. Garrett’s pop out finished off a 5–2 A’s win and heart-wrenching conclusion for Mets fans.

What seemed to be a harbinger of good things to come in 1974 and beyond instead became the high-water mark for the decade, as the franchise eventually sunk to tremendous lows. By the late ’70s, gone were Seaver, Koosman, high attendances, and any semblance of hope.

The 1973 Mets didn’t lack for uniqueness and historical signifcance. After all, the team featured three of the most beloved figures in New York sports history (Seaver, Mays, and Berra) at different stages of their baseball careers. Still, they’re often overlooked from discussions about great comeback stories, perhaps because they played in the shadow of the ’69 Miracle Mets, or because they are stigmatized by being among the worst teams (at leat record-wise) to have ever played in a World Series. But any club that can beat the talent-laden Reds and then battle the A’s (who would win a third straight ring in 1974) right down to the wire has much to be proud of.

The sands of time may have buried them in the annals of baseball history, but when you see a significant Mets home game with fans still holding signs reading “Ya Gotta Believe,” it’s proof that the spirit of ’73 still lives.