Set against the backdrop of a season salvaged at the dish plays out a less gratifying story line about shortcomings behind it. But what exactly do the young catcher's defensive woes mean, and should we even care?

The Mets front office has had its ups and downs in 2014. The Chris Young gamble certainly did not pan out. Meanwhile, free agent acquisition Bartolo Colon has been well worth the price of admission for sheer entertainment value alone, not to mention his relatively strong performance.

However, one of the quieter wins of the 2014 season has been the successful re-direction of Travis d'Arnaud. Why, just two short months ago it wasn't uncommon to hear questions—doubts even—about his long-term chances to stick at the major league level, let alone star as an offensive bulwark for a team short on firepower.

Now? Well, now d'Arnaud is one of the least pressing concerns on the minds of Mets fans. Hell, he's gone from being a major question mark to a relative given in about as short a span of time as one could ask for.

And yet, there's something that continues to hold us back from throwing caution to the wind and anointing d'Arnaud the next of the cornerstone catchers destined to take this club to the promised land: his defense.

Perhaps most noticeable has been his poor record preventing the stolen base. At just 20 percent this season, he rates in the bottom tier in baseball in throwing out baserunners. But what fans may not have noticed is that at about 23 seconds between pitches, the Mets have a generally slow-paced staff. Furthermore, caught stealing percentage is a high-variance statistic year-to-year. What I'm saying is that if throwing were the only concern we have reasons to overlook it.

But the crux of his defensive issues, going back to his initial call-up in 2013, has been his seeming inability to block baseballs. In fact, his tendency to flat-out whiff on relatively standard offerings has been, at times, downright confounding given his solid defensive profile. Based on what we've seen this season, it almost goes without saying that d'Arnaud ranks dead last in passed balls, tied with known butcher Wilin Rosario.

What's troubling about this is that unlike throwing, blocking pitches is a problem almost entirely inherent to the catcher. In this case there's no one to blame but d'Arnaud himself. And I mean that very literally; unlike Wilin Rosario who really can't help it because he probably doesn't belong behind the plate, d'Arnaud chooses this contemptible fate.

So d'Arnaud chooses to allow passed balls, you say? Well, a significant amount of d'Arnaud's passed balls have very clearly come as a direct result of his known proclivity for framing pitches. See for yourself:

While it's not really quantifiable, the theory certainly passes the eye test. So by choosing to frame those close pitches d'Arnaud is subjecting himself to more passed balls. Stop the framing, and the passed balls in turn will stop, right? Wrong.

Frankly, the passed balls are collateral damage. Whether or not d'Arnaud knows this, the positive value of the additional strikes that he steals with his exemplary framing skills outweigh the negative value of the additional passed balls they produce.

We know this thanks to the outstanding research performed by Max Marchi over at Baseball Prospectus wherein he effectively assigned run values to the various "non-quantifiable" components of catcher defense, a couple of those being framed pitches and blocked balls. Marchi's variousstudies get into the nitty-gritty, but based on his calculations, the value derived from pitch-framing dwarfs that which derives from pitch-blocking.

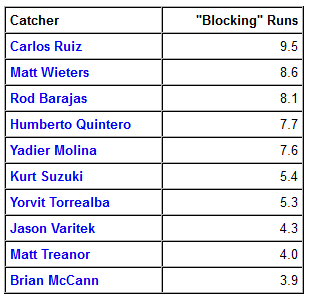

Specifically, the very best pitch-blocker over the four-year span Marchi analyzed (2008-2011) was Philadelphia's Carlos Ruiz. Utilizing linear weights, he determined that Ruiz generated 9.5 "Blocking" Runs -- far and away the highest total in that span:

Meanwhile, the best pitch-framer in baseball from 2008-2011 was Brian McCann:

Based on linear weights, the very best framers were worth, on average, over ten times as many runs as the top blockers.

The old saw that we often hear about when it comes to pitch-framing is that of Jose Molina and the Rays. You know the story: Molina can't hit his way out of a paper bag yet the club continues to make it a top priority to retain him, even deeming him worthy of a multi-year contract going into his age-38 season, based on the value of his until-recently undervalued pitch-framing skills. What's more interesting for our purposes is that, like d'Arnaud, Molina is actually a pretty terrible blocker. During that same four-year span, Molina cost his teams approximately six total runs, which is close to the bottom of the list.

Aside from the instructive trail blazed by forward-thinkers in St. Petersburg, there's also a burgeoning pattern worth calling out here: While the data points are still somewhat limited, the top of the pitch-framing list has a lot in common with the bottom of the pitch-blocking list.

In short, there seems to be an element of robbing Peter to pay Paul when it comes to framing pitches, except teams like the Rays have realized that Paul brings back much higher rates of return, so that trade-off is okay.

Further, it stands to reason that catchers like d'Arnaud know, but just don't care, that those extra strikes are costing them a few more passed balls. From Marchi's data we can see that the toughest pitches to block are those tagged 'in the dirt.' Most of the time these are breaking pitches that end up at the bottom of the strike zone. But the bottom of the strike zone also seems to be where an expert framer like Travis d'Arnaud makes his bones:

And here's a heat map from ESPN's Mark Simon quantifying what we're seeing with our eyes:

This is the area for which Mets C Travis d'Arnaud rates best at stealing strikes by our pitch tools pic.twitter.com/ZoCxZXpNZh

— Mark Simon (@msimonespn) August 10, 2014Put simply, d'Arnaud keeps on calling for those breaking balls in the dirt, difficult to block though they may be, because those are also the pitches he's going to have the best chance to 'steal' from his opponent. And to this point it's worked. According to Jeff Sullivan's recent evaluation of which teams have been helped and hurt the most by pitch framing in 2014 over at Just a Bit Outside, the Mets ranked in the top five in baseball due in no small part to Travis d'Arnaud.

So once again, my advice is this: Don't sweat the small stuff, the occasional passed ball. The upside may seem like only a couple of measly strikes, but as Sullivan points out, they add up fast.

*And now, because these are fun to watch, I leave you with some more truly spectacular framing: