Ya Gotta Believe.

"It was a joke, you know," Tug McGraw remembered.

"We were all laughing about it. It wasn’t meant to be serious, just something new, something different, in the middle of a slump."

The timeless exhortation, "Ya Gotta Believe," had its origins in a team meeting with famously dour Mets Chairman M. Donald Grant, who had put on his best face to express "belief" in his last place team.

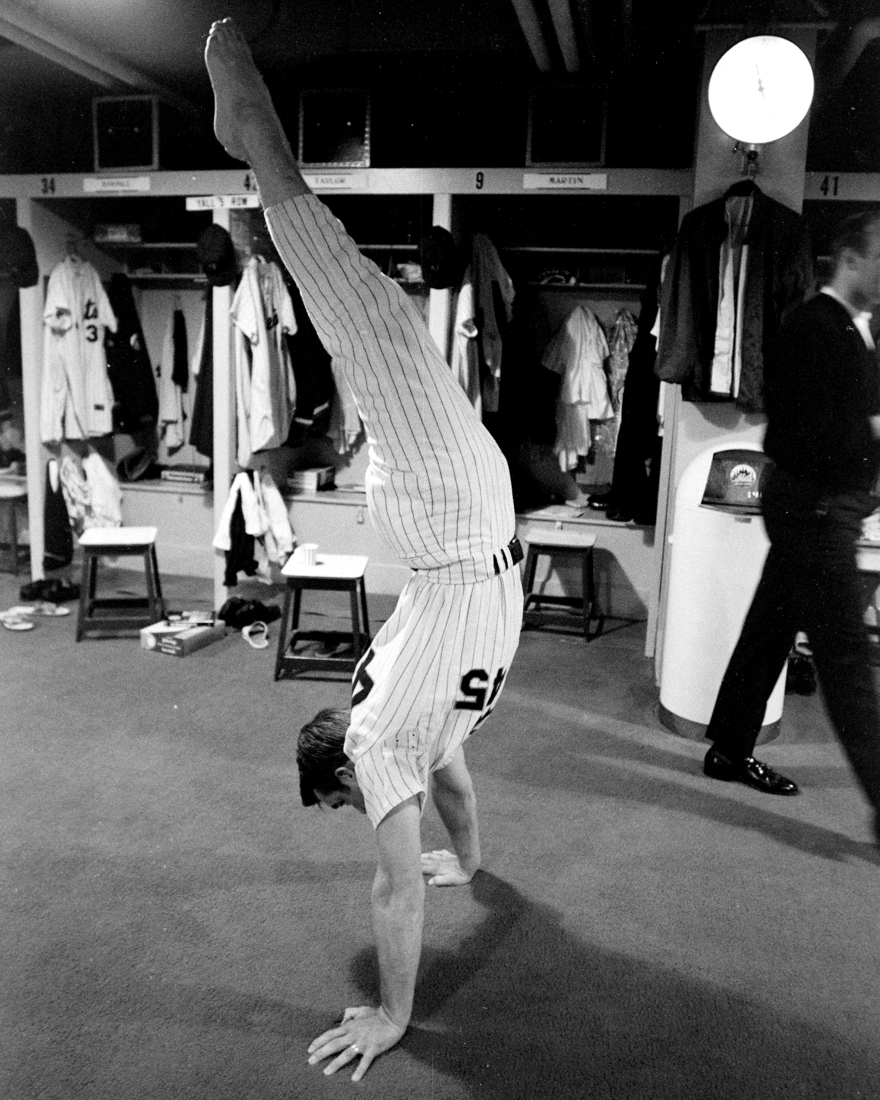

Tug said, "He threw that at us, and I sort of caught it, and as soon as the meeting was over, I started running around the clubhouse to each locker hollering at guys, ‘Do you believe?’ and ‘You gotta believe.’ And grabbing guys by the hair and pulling their heads up and yelling ‘Ya gotta believe!’ And everybody thought I was crazy.’"

Grant, for his part, though he was being mocked, and pulled McGraw into his office to tell him to start winning games or pack his bags.

"He wasn’t laughing." This was 1973.  Photo: New York Daily News Archive

Photo: New York Daily News Archive

Frank Edwin McGraw was born in Benitez, California, in 1944, and was called "Tug" on account of his feisty breastfeeding.

"I never answered to another name," said McGraw.

His mother, who suffered from bipolar disorder, was emotionally and physically abusive. She abandoned the family while on weekend leave from an institution, leaving Tug with his father. "Big Mac" was a butcher, trucker, and fireman, who in those years worked as an operator at a water treatment plant.

After high school Tug attended community college. In 1964 he was drafted by the Mets. They did so at the insistence of Tugs big brother Hank, who was drafted by the Mets in 1961. Hank was a catching prospect but never played in the major leagues. He was a nonconformist who would not cut his hair or brook racial segregation, which caused him to be suspended by the team for months.

After a dominant year mostly in the Florida Rookie League – his first start was a 7-inning no hitter – Tug broke camp in 1965 with Casey Stengel’s Mets, and struck out Orlando Cepeda in his April debut.

"His bat looked like the biggest bat I’d ever seen in my life," McGraw remembered. "It looked like a telephone pole."

Stengel made effective use of the rookie from the bullpen. When the Old Perfessor retired in July, McGraw was given a chance to start, throwing a two-thirds-on-an-inning laugher at Wrigley Field. Tub made up for it the following month by becoming the first Met to ever defeat Sandy Koufax. McGraw finished the year 2-7 with a 3.32 ERA.

In the winter McGraw trained as a rifleman with the U.S. Marines, becoming – in his words – a "trained killer," though describing himself as a "dove" on the subject of Vietnam. (Speaking of the 60s, when asked how Houston’s new AstroTurf compares to grass, McGraw said he didn’t know. He never smoked AstroTurf.) He also learned the art of haircutting, which he later demonstrated by shaping the coiffure of Ralph Kiner.  Photo: Focus on Sports / Getty Images

Photo: Focus on Sports / Getty Images

McGraw suffered arm trouble in his sophomore season, which he attributed to his having bulked up as a Marine. He spent nearly all of 1966 and 1967 in the minor leagues, where he learned the screwball from teammate Ralph Terry.

"It worked," he said of Terry’s grip. "In the pepper game the next day, whoa, there it was. I stuck with it, and the next thing I knew, I had my pitch."

Nevertheless, fellow Marine Gil Hodges did not give McGraw a shot until 1969, and only after the Mets had left him unprotected in the 1968 expansion draft. He made the team out of spring training as the left-handed complement to the veteran righty Ron Taylor, and except for some ill-fated fill-in starts for an injured Jerry Koosman, he proved a reliable bullpen piece.

McGraw pitched steadily then caught fire as the team made its improbable run at the division-leading Cubs. From May 31 to June 20 he saved five games in seven outing as the Mets won 11 straight. From July to season’s end he had a 0.79 ERA in 49 1/3 innings, including four scoreless innings on the night the Mets secured their miraculous pennant. He saved Game Two of the NLCS, but was not called on against the Orioles and their powerful, mostly right-handed lineup, popping up only to drink champagne.

And with that he had his first taste of the impossible.

Though he stumbled the next year, McGraw posted a better-than-Seaver ERA of 1.70 in 1971. Pitching strictly from the bullpen, he struck out a career-best 8.8 batters per nine innings and put up 4.1 rWAR. By ’72 he was the team’s regular closer, more than doubling the franchise record by recording 27 saves. He also nudged his career-best rWAR up to 4.3, and was rewarded with the opportunity to strike out Reggie Jackson in that season’s All-Star Game.

After consecutive years in third place, the Mets thought they had a chance in 1973.

"We got the front line to win it, if we don’t have any serious injury problems," McGraw predicted. Yogi Berra’s bunch was in 2nd place as late as the end of May. On July 31, they were in last. The injuries came, and came hard, and McGraw for his part was pitiful; he had a stretch of 26 games with a 8.07 ERA in which the opposition scored three-plus runs against him six different times.

Then he hopped around shouting "Ya Gotta Believe!" and it all turned around! (Hey, it’s true. If you want to infer causation, that’s up to you, but sequentially speaking, it happened.)

The Mets were not gangbusters in ’73. At 82-79, they turned in the most mediocre record ever to earn its team a pennant, Still, their late-summer surge was indeed remarkable, and their late-inning lefty was a big part of it. McGraw picked up either a win or a save in 17 of his last 19 appearances, pitching to a 0.88 ERA, as the Mets closed the season by going 24-9. In those last weeks, as fans hoisted signs emblazoned with what had already become Tug’s trademark, Tug and his wife Phyllis also gave birth to their second child.

Tug was not immediately needed in the NLCS against the Reds, as Seaver, Matlack, and Koosman each went the distance, though Koos took the loss. He put in five adventurous but scoreless innings in the last two games (3 K, 3 BB, 4 H), and stood atop the hill as the Mets punched tickets to Oakland for the World Series, heading West "denounced, damned, cheerful, mobbed, written up, screwed up—and bombed out of our minds."

In the first two games of the World Series, McGraw pitched eight innings – two-plus scoreless on Saturday and six innings on Sunday. In the Sunday game, he was pulled after giving up a triple and walk to start the twelfth inning, but the Mets hung on to preserve a 10-7win.

In Flushing, he pitched a 1-2-3 ninth and a scoreless tenth in the first postseason night game in Mets’ history, then after a game off threw 2 2/3 innings in a 2-0 Game Five win that put the Mets a game away from glory. Back in Oakland, he pitched one more inning, bringing his World Series total to a ridiculous 13 2/3 in 5 games (with 14 Ks, 9 BB, and 4 ERs), but of course it wasn’t to be. It was the A’s turn to roar from behind, beating the Mets 3-1 and 5-2, dashing the hopes of true believers everywhere.

The hangover was ugly. In 1974, the Mets’ dreadful first half would not again be spun on its heel, and an ailing Tug McGraw ignominiously gave up four grand slams and eight other homers in 88 1/3 innings work. Without much hope – or belief – the Mets "put me on display," Tug said. Despite nagging injuries, they started him. It was an attempt, he thought, to fake confidence in his health before dumping him on the trade market. The swap came at that year’s Winter Meetings, moving McGraw, Don Hahn, and Dave Schneck to the Phillies for Del Unser, John Stearns, and Mac Scarce.

It was a bummer. "Everything I own has ‘Mets’ stamped on it," he said.  Photo: B. Bennett / Getty Images

Photo: B. Bennett / Getty Images

A hundred miles south, McGraw had surgery to remove "a benign mass of gristle" from his shoulder – providing America the yet-unused band name, Benign Mass of Gristle – and went on to pitch a decade with the Phillies, racking up 22 saves and a 2.39 ERA against his Amazin’ former team, both personal bests (except for his 1.62 ERA against the Phillies as a Met.) In 1980, Tug had a year to match or exceed his fantastic 1971 and 1972, leading the Phillies to their first postseason series victory of any sort in a nearly 100 year history as well as their first World Series title.

Tug retired in 1984 after 19 seasons almost evenly split between the division rivals. He collected 12.8 rWAR in New York and 8.2 in Philly, and is beloved in both cities. Though his stretch of ERA+ of 163, 123, 201, and 198 from 1969-1972 might be his peak years, the last months of 1973 and "Ya Gotta Believe" were certainly his peak act of poetry. Tug was inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame in 1993. A decade later, he was diagnosed with brain cancer, given months to live, and participated at events in both Veterans and Shea Stadiums before succumbing to the disease.

Tug’s marriage had fallen apart and a year before his death he described himself as a "former world champion baseball player – at one time the highest-paid relief pitcher in the game of baseball – and I was homeless, penniless, and living in a budget motel." But in his last year he’d found a mentoring role with the Phillies organization, and strengthened a once-nonexistent relationship with Tim McGraw, the country singer, who was Tug’s son from a fleeting relationship in his minor league days. Tim sat by his father’s bedside at the end.

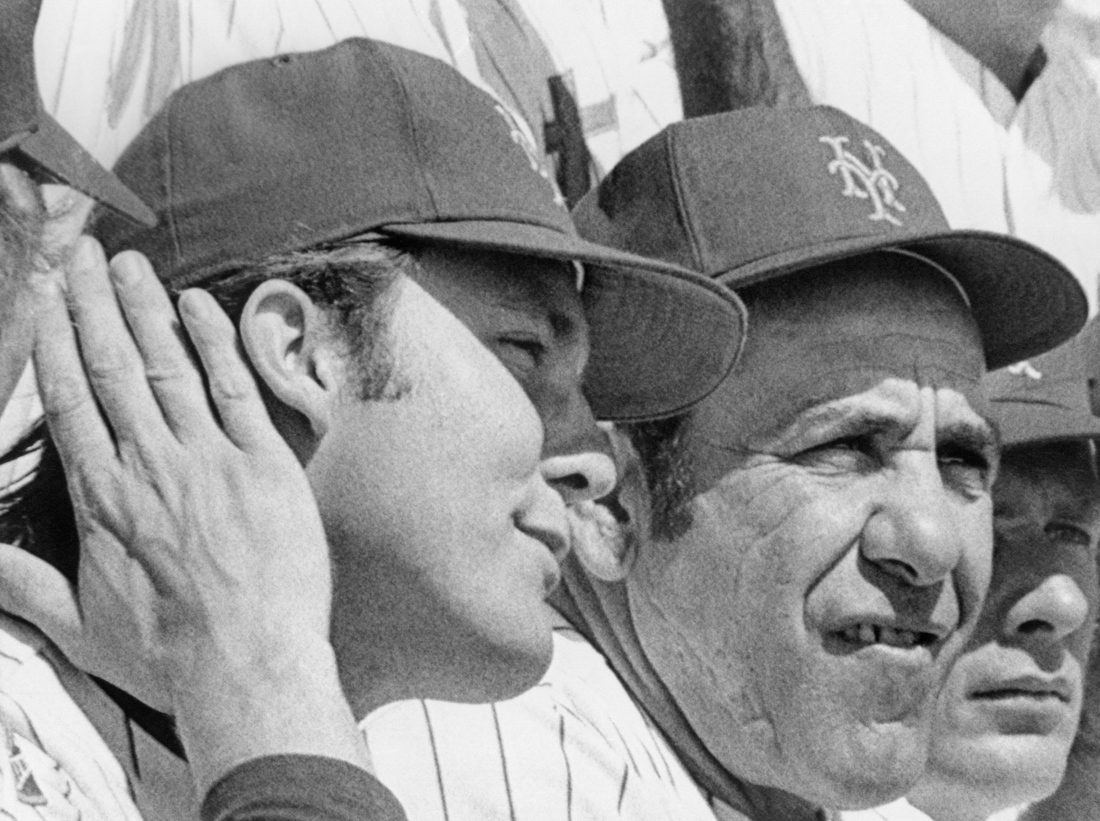

Tug McGraw pitched 19 years in the majors. Perhaps no day was sweeter than a cold, rainy one in Chicago in front of just 1,913 fans. It was October 1, 1973. Tom Seaver gave up a go-ahead homer in the seventh inning. Yogi Berra took the ball from the Franchise and gave it to Tug McGraw. What followed was a clean seventh, a clean eight, and after a single in the ninth, a strikeout and a line-drive double play to clinch the pennant for the "denounced, damned, cheerful" Mets.

According to Mets beat writer Jack Lang, "McGraw kept yelling, ‘You gotta believe!’ and even Grant, who was also in the clubhouse, did not mind now."  Photo: Ray Stubblebine / Getty Images

Photo: Ray Stubblebine / Getty Images