Clik here to view.

Capsule comments on each of the players whose fates will be revealed in January -- with derision reserved for the steroids-obsessed puritans of the BBWA.

Mike Piazza: The best all-around hitter among catchers has been weirdly attractive to the steroids scolds, who have gone so far as measuring his back hair in pursuit of convicting evidence. (If back hair were evidence of having super-powers the nation's 45-year-old men would have long since banded together to form the Justice League of Flatulence.) In his book, Piazza ‘fessed to using Androstenedione and Ephedra, supplements then legal in baseball, but denied using anything else. Just for argument's sake, let's say that Piazza did use. Heck, let's say that he bolted the whole medicine cabinet from aspirin to Zantac. Given that so many players have failed tests, the guys we know used, apparently reaped no benefit whatsoever, what percentage of Piazza's accomplishments would you like to credit to the drugs? Be fair now, remembering all those faceless minor leaguers who have been suspended, and even those world-class runners who have been caught after making times tenths of a second better than the field. We cannot quantify what these things do for a ballplayer. That doesn't stop people from trying, or even speaking authoritatively on the subject, but don't you believe them.

A failed attempt to cheat is in no way morally superior to not cheating, but I do think we can stop pretending that the numbers are illegitimate, and at that point some of the high dudgeon can be fanned away on the basis that the so-called steroids era was about an ethical lapse rather than a major crime.

In his latest dispatch from the North Pole, former New York Times reporter/PEDs obsessive Murray Chass quotes an interview conducted by Jeff Pealman regarding "evidence" of Piazza's usage:

"There was nothing more obvious than Mike on steroids," says another major league veteran who played against Piazza for years. "Everyone talked about it, everyone knew it. Guys on my team, guys on the Mets. A lot of us came up playing against Mike, so we knew what he looked like back in the day. Frankly, he sucked on the field. Just sucked. After his body changed, he was entirely different. ‘Power from nowhere,' we called it."

Damning, right? Maybe, but also maybe not. Piazza was drafted in 1988 and made his minor league debut in the Low-A Northwest League. He was in his age-20 season, a time in life when many ballplayers are still maturing physically. He slugged .444 in 57 games that year, which was roughly 100 points above the league average. Piazza struggled at High-A Vero Beach in 1990, hitting .251/.281/.390, but the league as a whole hit only .245/.326/.330, so he was still showing above-average power. He started hitting for real in 1991 at Bakersfield of the California League, averaging .277/.344/.540. Now, the quote above doesn't tell us when Piazza's "body changed," but those that would argue that he did something illicit somewhere in that period have to account for (a) the possibility that Piazza matured as he aged from 20 to 22, (b) that he devoted himself to a bodybuilding regimen that would have paid off in improved strength with or without chemical assistance, (c) that he had above-average power all along, and very likely (d) all of the above. We can also add in (e) hearsay is not the same as evidence.

It was in 1992 that Piazza added the final component of his repertoire and started hitting .350, and I guess we can ascribe that to the juice as well. PEDs are the all-purpose explanation, transforming puny Bruce Banner into the Incredible Hulk. It's science!

Image may be NSFW.

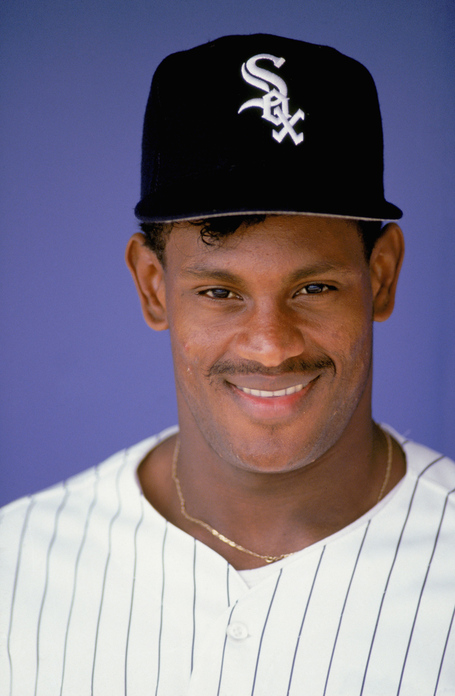

Clik here to view. Tim Raines, 1984. (Getty Images)

Tim Raines, 1984. (Getty Images)

Tim Raines: What is it about the 1980s that so confuses the so-called professional observer? Jack Morris's mustache seemingly cast some kind of hypnotic spell that blotted out the work of better players like Raines and Alan Trammell. I won't recapitulate Raines' qualifications here; they should be more than apparent. He had the misfortune to be the second-best leadoff man of his time when the best of all time was playing in the American League. That in no way made him less than an all-time great in the same way that Lou Gehrig was not at all diminished by playing at the same time as Babe Ruth. He also had a cocaine problem, but sought help on his own and was never sanctioned by baseball. Perhaps that's what is keeping him out, or it could be that his talents are somehow too subtle to be appreciated by the same voters who enshrine slugger after slugger. Raines averaged 11 home runs a year and yet scored 102 runs a season. These are the kinds of skills the PEDs police are supposed to appreciate.

Kenny Rogers: Bobby Valentine stuck Rogers in the bullpen for the first four years of his career, costing him a chance to push his career win total a little higher, though who knows -- perhaps he wouldn't have had high victory totals late in his career if he hadn't been used lightly earlier on. Rogers' inconsistency means it's not something we have to think too hard about.

Curt Schilling: As with many great players, he's apparently a better athlete than a human being (or at least a businessman). But let us judge not lest we be judged. Schilling didn't reach the 300-win level, but if you can find where it is written that the number of the hall shall be 300 and not 200, well, phone your bible studies class at once. P.S.: He was a key part of four World Series teams and was 11-2 with a 2.23 ERA in 19 postseason starts.

Richie Sexson: Fewer than 100 players have retired with a career slugging percentage of .500 or better. That Sexson was one of them without anyone ever suggesting he was a great or even a particularly good player suggests just how debauched post-strike offensive levels became.

Lee Smith: In the early 1980s, before the idea of a the "closer" evolved and a team's best reliever was used in the pitch-anytime fireman role, Smith was as valuable as some starting pitchers, throwing 90 to 110 innings a year. Used that way, he had fewer saves (he led his league in saves just once between arriving in the majors in 1980 and 1990) but had a greater impact on games. Looked at from the vantage point of wins above replacement, Smith was among the 25 or so most valuable pitchers in baseball in the years 1982-1990, the upper boundary marking his final season of 80 or more innings. If his whole career had been spent in that mode he might well have had a stronger case for the Hall of Fame, but over the rest of his career had more saves, surpassing 40 three times and leading the league in three seasons, but he had less of an impact -- the three 40-save seasons combined had less value than Smith's 103.1-inning campaign of 1983.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Lee Arthur Smith (Getty Images)

Lee Arthur Smith (Getty Images)

J.T. Snow: You can make fun lists of players who were blocked by their betters, for example all the catchers the Yankees traded because they had Yogi Berra (Sherm Lollar, Gus Triandos, and Clint Courtney among them) or first basemen run off by Don Mattingly. That list begins with Steve Balboni and also includes Hal Morris, Orestes Destrade, and Mr. Snow, who was traded for Jim Abbott in 1992. He wasn't a Hall of Famer, but given that his primary employer had Jeff Kent and Barry Bonds around, he didn't have to be one.

Sammy Sosa: Another guy everyone assumes juiced, and when you look at a chronological series of headshots it's hard to miss his skull gradually inflating from normal human to Jack-o'-lantern proportions. Again, turning oneself into a gourd is evidence of the intention to cheat, not successful cheating, and it is worth remembering that there were many other environmental changes at work in the game during Sosa's heyday that combined to accentuate his great strength and make the achievement of such bizarrely inflated numbers possible. We accept that Babe Ruth and Roger Maris benefitted from environmental changes (in the former's case the introduction of the lively ball in 1920 and the rabbit ball in 1930, while the latter had expansion and an extended schedule), but for the modern guys it had to be purely chemical so be it.

Sosa was initally a more versatile player than the musclebound slugger of his later years suggested, an athletic right fielder (though error-prone,) and a good enough basestealer to reach the 30-30 mark on two occasions. As his power increased, his other skills declined, so that with the exception of 2001, his overall offensive performances are not that special by the standards of his era. His celebrated 1998 campaign (.308/.377/.647 66 home runs), when adjusted for Wrigley Field, is virtually indistinguishable from that of roughly 10 other players (see table below). Some may look at his 609 career home runs and see an automatic argument for enshrinement, but as I've said again and again throughout this three-part series, no number should represent a reason to forego the labor of critical thinking. This is consistent with the view that what the players got out of the bottle or the syringe was far less important than systemic changes in the game itself. Sosa's skill set meant those changes were reflected in inflated home run totals, but considered holistically, his numbers are typical of the best players of the era, clean and/or juiced.

| The Second Tier: Sammy Sosa and His Peers, 1998 | ||||||

| AVG | OBP | SLG | HR | OPS+ | oWAR | |

| Mark McGwire | .299 | .470 | .752 | 70 | 216 | 9.2 |

| Barry Bonds | .303 | .438 | .609 | 37 | 178 | 7.2 |

| John Olerud | .354 | .447 | .551 | 22 | 163 | 6.2 |

| Sammy Sosa | .308 | .377 | .647 | 66 | 160 | 6.3 |

| Jeff Bagwell | .304 | .424 | .557 | 34 | 158 | 6.0 |

| Larry Walker | .363 | .445 | .630 | 23 | 158 | 5.8 |

| Moises Alou | .312 | .399 | .582 | 38 | 157 | 5.9 |

| Andres Galarraga | .305 | .397 | .595 | 44 | 157 | 5.6 |

| Greg Vaughn | .272 | .363 | .600 | 50 | 156 | 6.1 |

| Gary Sheffield | .302 | .428 | .524 | 22 | 155 | 4.7 |

| Mike Piazza | .328 | .390 | .570 | 32 | 152 | 6.4 |

| Vladimir Guerrero | .324 | .371 | .589 | 42 | 150 | 5.7 |

Frank Thomas: If Ted Williams had played in the 1990s, this is what his numbers would have looked like. The Big Hurt had little defensive value, but then, neither did Williams. It didn't matter.

Mike Timlin: When Timlin reached the major leagues in 1991, only two pitchers had appeared in a thousand games -- Hoyt Wilhelm and Kent Tekulve -- and three others had pitched over 900. There are now 15 pitchers in 1,000-game territory, Timlin himself having reached number eight on the career list, and eight in 900-land. LaTroy Hawkins seems likely to reach the millennium mark, and Kyle Farnsworth, he of the rising fastball -- rising out of the park, that is -- and 6.1 career WAR may yet get to 900. Timlin got the most out of his career, not only pitching in all those games but going to four World Series and finishing on the winning side all four times.

Alan Trammell: Just as Trammell was establishing himself as an all-star-level player, rival shortstops blossomed and cast him into shadow. Robin Yount won the 1982 AL MVP award with one of the best offensive seasons a shortstop ever had, and in 1983 Cal Ripken did the same. With the Tigers rampaging through the American League in 1984, Trammell should have been next in line. Though he hit .314/.382/.468, a midseason injury and the voters' fascination with Willie Hernandez meant that he got only lukewarm support. He should have won in 1987, but then the voters just missed it, getting suckered in by George Bell's high home run and RBI totals. Thus his lack of Hall of Fame support is a case of double jeopardy: they fail to respect him now because their predecessors didn't respect him then.

I've tried to avoid utilizing WAR too often in this series because it frightens the unenlightened, but in terms of career value Trammell ranks eighth among shortstop. With the exception of Derek Jeter, not yet eligible, every other player in the top 16 is in the Hall, including Barry Larkin, who finished tied with him. He's going to get in, whether via the BBWAA or the Veterans Committee that reconsiders their oversights; they might as well get it right while he's still alive to enjoy it.

Larry Walker: It seems certain voters will struggle with Rockies players of the pre-humidor era, but it seems obvious that not every player who was transported to altitude turned into Walker. His 1997, in which he hit .336/.443/.733 on the road ranks among the best single-season performances of the postwar era. Walker wasn't durable, and Troy Renck of the Denver Post wrote recently that while he viewed Walker as the best player he ever covered, the outfielder lacked passion and often opted out of the lineup. The same was said about Rickey Henderson when he was in his prime, which leant a palpable irony to his holding on to his career until he was 44 and couldn't hit anymore. Walker only played in as many as 150 games once in his career. That said, he packed a great deal of production into the games he did play, enough to be a four-time all-star, seven-time Gold Glove winner, and win an MVP award with a third-place team. I respect Renck's point of view that Walker could have been more than what he was had he been more committed, but it seems shortsighted to let that completely invalidate the exceptional quality of what he did do.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Larry Walker (Getty Images)

Larry Walker (Getty Images)

More from SB Nation MLB:

• Rob Neyer's (fake) Hall of Fame ballot includes Bonds, Clemens

• Baseball Hall of Fame profiles:Curt Schilling | Larry Walker | Edgar Martinez

• ‘No idea’ when A-Rod decision will be made

• SP Masahiro Tanaka coming to MLB | How many years will he get?

• Death of a Ballplayer: Wrongly convicted prospect spends 27 years in prison